Mining in Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia, the colonial name for Mi’kma’ki that is the unceded land of the Mi’kmaq, has a long and often tragic mining history, much of it built on the backs and the blood of miners.

Just a quick note: mineral rights in Nova Scotia are owned by the government, not the landowner. This is explained here.

Choose a tile below to learn more.

A short history of mining in Nova Scotia

A quick perspective and overrview of mining in Nova Scotia.

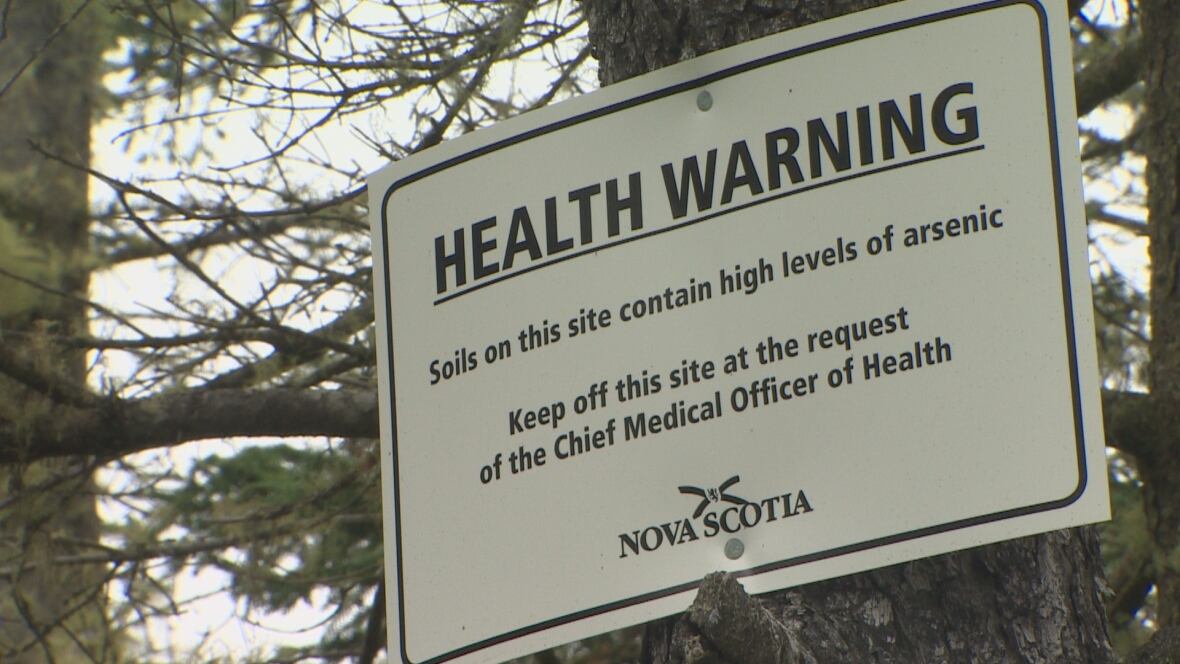

Gold Mining

Gold mining has a long history in Nova Scotia. The province is experiencing its fourth gold rush with all the associated consequences for the environment and public health.

Uranium Mining

Nova Scotia has had a ban on uranium mining since 2009. Tim Houston’s PC-government lifted the ban in 2025 amid protest.

Hydraulic Fracturing (Fracking)

The hard-fought battle to keep fracking out of the province was won in 2013. Tim Houston’s government reversed the decision and lifted the ban on fracking in 2025.